How our use of concrete defines and creates the amount of happiness

contained inside buildings.

Concrete is used to build prisons, which invoke loneliness.

Concrete is also used to build hotels, which invoke joy.

Part I

Facades of Joy

As a family rooted in Catholicism, our yearly tradition involves attending Simbang Gabi, the final Eucharistic celebration before Christmas. This year, we gathered in the Ballroom of the Diamond Hotel, enveloped in the warmth of the festive season. Amidst the atmosphere of joy, a moment of solemnity emerged as the priest's words echoed through the hall.

"Pray that those in isolation—prisoners—experience the joy brought by your birth."

This simple yet profound statement struck a chord within me, prompting a deeper contemplation. It forced me to confront the stark reality of the loneliness and isolation experienced by prisoners, especially during a time meant for togetherness and celebration like Christmas. It made me reconsider the duality of concrete structures: while they are crafted to facilitate joyous family gatherings in places like hotels, they are also employed to construct environments that enforce isolation, such as prisons.

This reflection has led me to examine the world through a different lens. Through a series of photographs, I aim to juxtapose the contrasting facades of structures that exude happiness with those that signify isolation. This exploration intends to shed light on what individuals confined in darkness and isolation might be missing, prompting a deeper societal contemplation.

Part II

Inside the Concrete

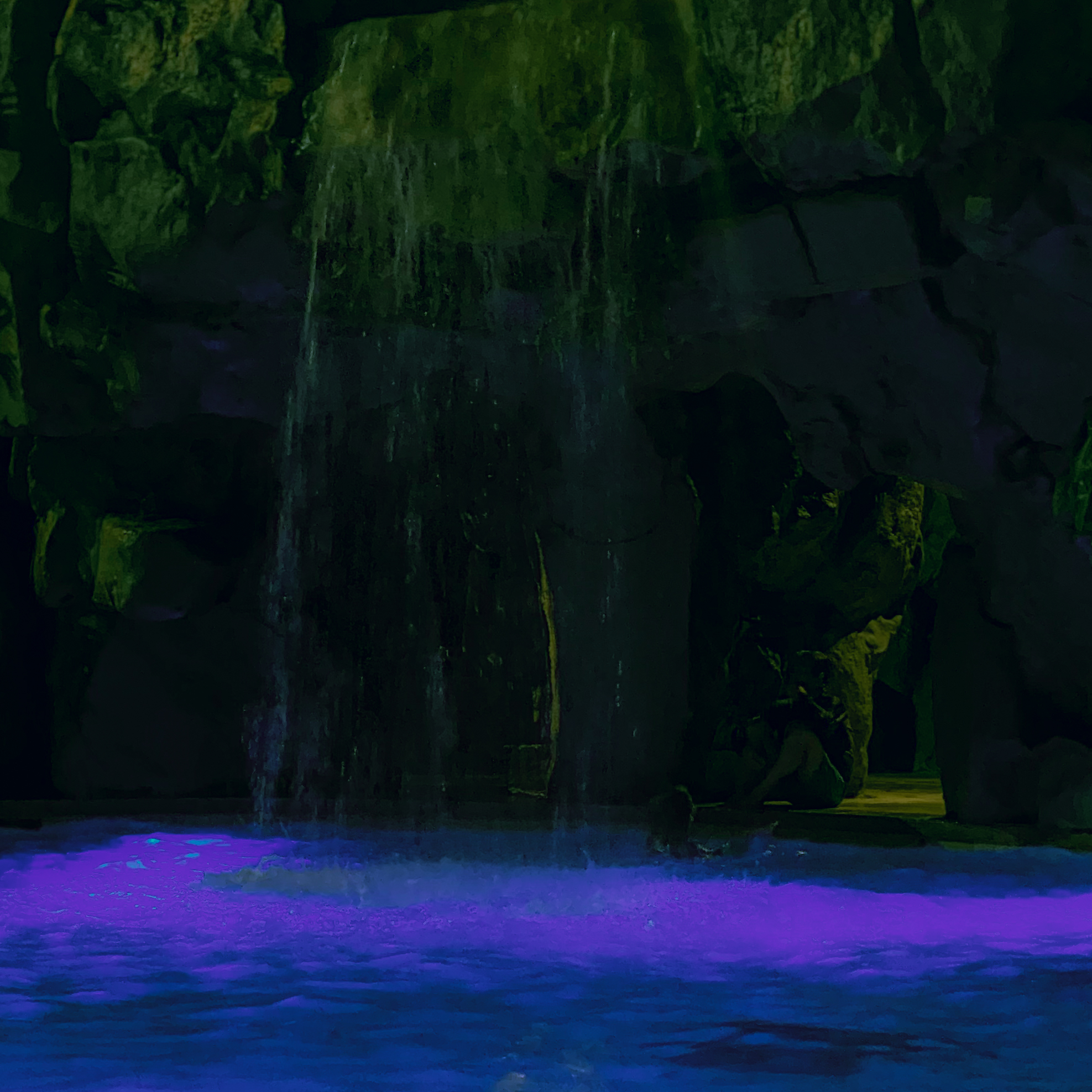

Since I was in fifth grade, about 11 years old, we would enjoy our Christmas in the Diamond Hotel in Pasay City, Philippines. We would always stay there for a night to enjoy the Simbang Gabi, swim, eat, and relax. But most important of all, spend time together.

For about four years, the lockdowns brought by the COVID-19 pandemic put our short staycations in Diamond Hotel to a halt. For four years, it forced us to stay in our homes. However, our house is not uncomfortable, in a sense. Yet the idea, anticipation, and comfort brought by the hotel and our yearly tradition made Christmas very anticlimactic.

After years, yesterday was the first time we spent time in the hotel again. In this section, I document the scenes and places that bring me comfort, scenes that remind me of togetherness—things that people in isolation cannot seek.

Part III

Facades of Isolation

As we went home, the comfort and joy brought by the holiday remained. However, the stark realization of the existence of people who cannot seek or even ever-so-slightly feel the comfort brought by the holiday also remained.

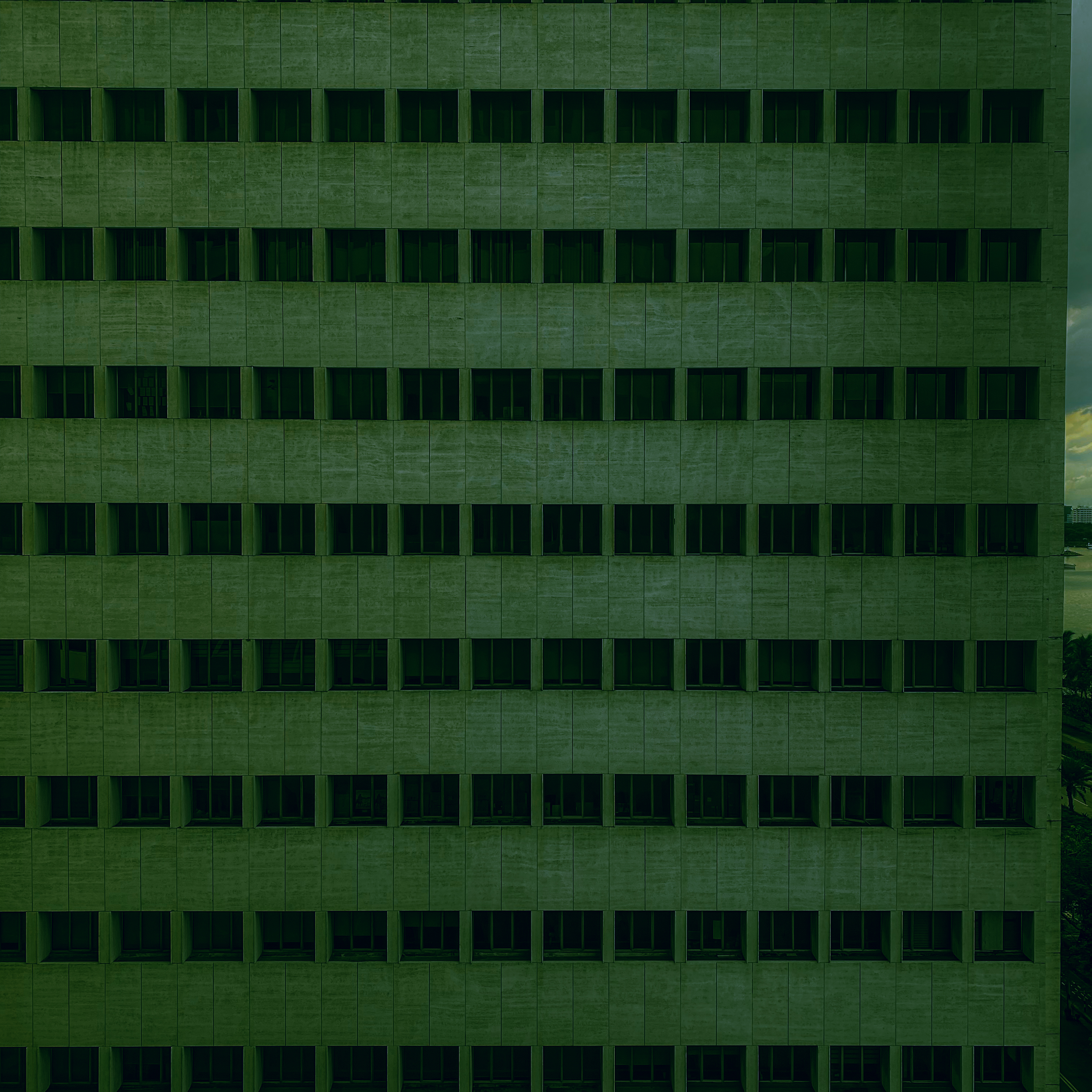

In this section, I collected scenes that spoke of isolation: facades with unlit, empty, and bleak windows, an empty shopping mall floor with a large window overlooking the joyous city.

This section constantly reminds me of the idea that we should cherish every second of togetherness, no matter how big or small it is. Though we can experience the true feeling of isolation prisoners feel on the day of togetherness, keeping this idea in mind should help us cherish the littlest things.